Context

Just as Europe's Beating Cancer Plan faced its critical 2025 review which showed it is unlikely to meet its goal of offering cancer screening to 90% of eligible citizens by 2025, Exact Sciences has just announced the launch of the Cancerguard™ multi-cancer early detection (MCED) test, reigniting debate around the technologies ability to revolutionize early cancer screening. Despite the excitement, it is important to recall the experience following the introduction of GRAIL's Galleri test in 2020, when initial enthusiasm gave way to increased caution. The question now is whether incremental advances in MCED are enough to overhaul cancer screening, or whether the path forward will require a more measured, stepwise integration?

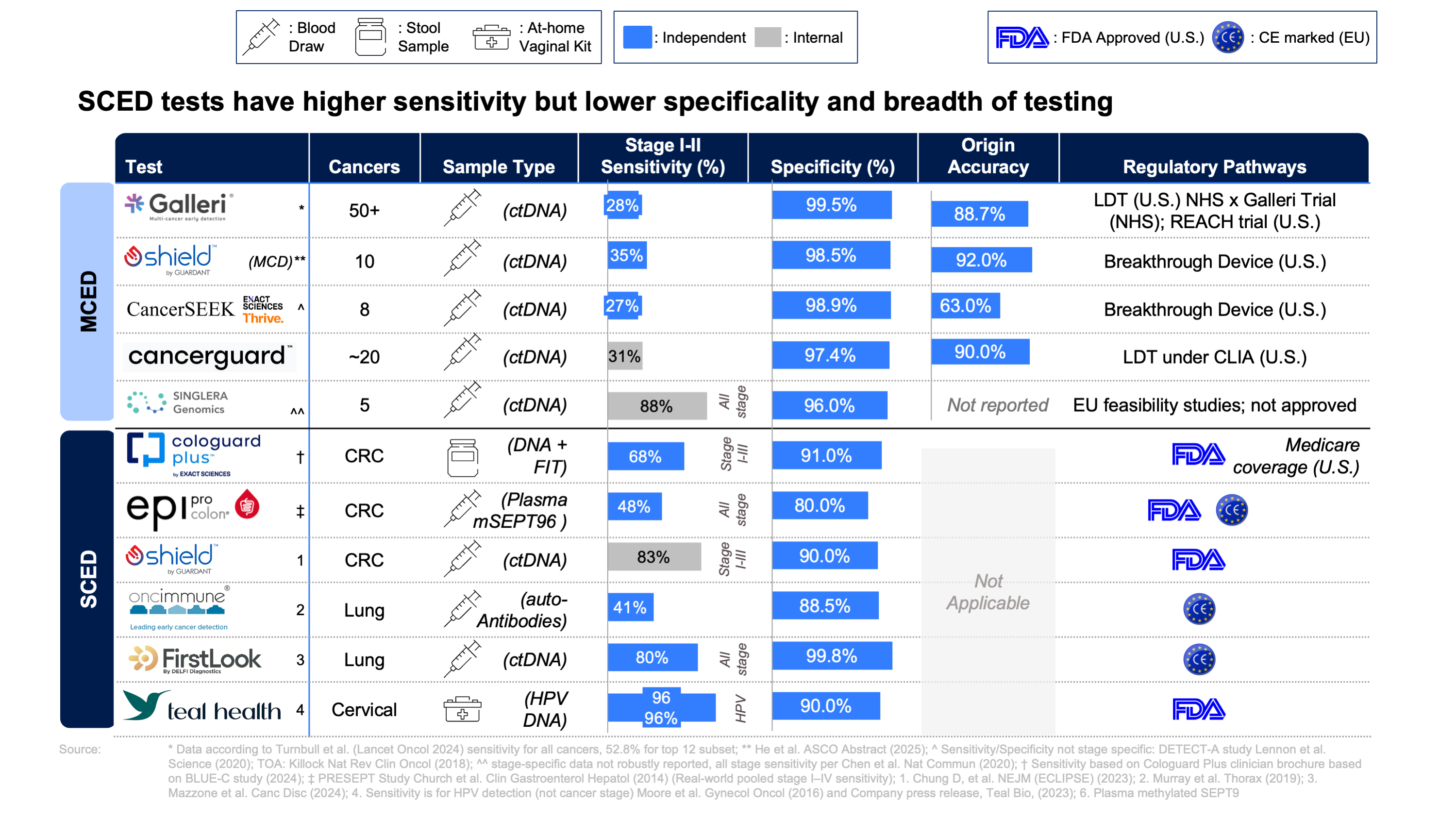

In May, the NHS made headlines as the first health system globally to launch liquid biopsy testing at scale, but with a focus on single cancer early detection (SCED), pancreatic initially and later breast after previously partnering with Galleri for an MCED trial. Meanwhile, in the U.S., payers have also signaled support for SCED: Exact Sciences Cologuard Plus secured favorable Medicare pricing, highlighting its strong sensitivity for early stage colorectal cancer (CRC) detection (88 and 93% sensitivity for stage I and II respectively.

This momentum for SCED stands in contrast to ongoing developments in multi-cancer early detection (MCED) testing in Europe. In 2024 the NHS deferred plans for a large-scale pilot program of MCED testing rollout opting to await final data from the trial, as preliminary results fell short of expectations. The tempered sentiments around MCED were echoed by Turnbull et al.’s critical Lancet publication which reported more conservative results for detecting true stage I-II cancers than previously published (sensitivity 27.5%; 95% CI) as well as an 88.7% accuracy of identifying tumor origin.

Meanwhile, commercial turbulence- including a class-action lawsuit from investors questioning the validity of claims, and the European Commission’s anti-competitive challenge, which led to Illumina’s spinoff of GRAIL in 2024 and a reported $2 billion net loss, added further complexity to the landscape.

Given these circumstances, a key question arises: does MCED represent the future of cancer screening or will incremental improvements in risk-stratified, single-cancer testing dominate in the short to medium term?

NHS first in world to roll out ‘revolutionary’ blood test for cancer patients.” – NHS England

Early Detection Saves Lives

Despite the method of testing, recent data underscores the urgency of advancing cancer detection and prevention. According to the EUROCARE-6 study in The Lancet Oncology, an estimated 5% of Europeans live with a cancer diagnosis. Meanwhile, OECD reports suggest that healthcare expenditure has outpaced inflation by 3-4% annually over the past decade as systems strain under growing disease burden, population growth, and economic pressures.

Santucci et al. exposed a critical paradox: despite therapeutic advancements reducing age-standardized mortality rates (ASR), the absolute number of European cancer deaths continues to rise (~1.3M in 2024), driven largely by an aging population. More concerning however, is the increase in ASR for CRC in 25-49-year-olds, a group largely excluded from national screening programs.

As a result, Europe faces a twofold challenge: an expanding at-risk population and increasingly strained health systems, making the case for preventative care a strategic imperative. The foundational principle of public health holds true: early detection saves lives (and money). For example, data presented at the 2022 ISPOR conference highlighted a four times lower total cost of treating cervical cancer at stage I than at stage IV. Yet the reality is sobering: Cardoso et al. found that ~87.3% of CRCs across 9 EU countries were detected outside of organized screening programs, ~56% of these at stages III-IV, a gap driven by resource and socioeconomic limitations. Additionally, Europe is not a monolith: Eurostat and SAPEA have revealed that while over 80% of eligible women in Sweden, Finland, and Denmark underwent breast cancer screening in 2023, only 14.5% did in Greece (Figure 1). Moreover, breast screening coverage (~95%) outpaces cervical screening (~72%) despite the latter’s establishment in the 1970s.

The absolute rise in cancer deaths, emerging incidence in younger patients and the persistence of late diagnosis have exposed critical gaps in current EU screening protocols. Against this backdrop, “Europe's Beating Cancer Plan” targeted that by 2025, 90% of all eligible patients would be offered screening for 6 cancers, representing ~55% of total cancer incidence. However, this goal now appears aspirational and is now targeted for 2030. Challenges remain like cultural barriers (e.g., cervical smear acceptability), resource barriers (e.g., colonoscopes, mammogram and technician availability) and the logistical complexity of managing multiple protocols for different cancers. Furthermore, evolving EU demographics complicate this target: 2023 saw a 4.7% increase in first-time residence permits issued to non-EU citizens while Bozhar et al. report an underutilization of screening services by this group.

Enter MCED testing. A novel ctDNA-based testing approach touted as a potential game changer by proponents. With MCED tests like GRAILS Galleri, 50+ cancer types are analyzed simultaneously through a simple blood draw and can be detected at earlier stages than traditional methods.

MCED Testing: A Paradigm Shift or Premature Innovation?

MCED promises economic benefits: Hackshaw et al. modelled an improvement in the true-positive:false-positive (TP:FP) ratio from 1:18 (with a diagnostic cost of £10,452 per cancer detected) to 1:1.6 (£2,175) in UK screening pathways. However, it's broad-based rather than risk-stratified approach expands the screening population. Compounded by the imprecise determination of cancer signal origin, this risks a surge in downstream investigations that strain capacity and budget.

Clinically, Exact Sciences claims that Cancerguard can lead to a 42% reduction in stage 4 diagnosis and an 18% decrease in overall mortality. Other simulation studies project modest average gains from MCED use (~0.14 life-years and 0.13 QALYs per screened person) based on surrogate endpoints such as stage-shift. Stage shift metrics, however, are vulnerable to lead-time bias i.e., increasing the time known to have cancer without necessarily extending the time surviving it. False positives compound the challenge, driving cascades of imaging and invasive procedures that strain both patients and systems, particularly in early cancer, the primary screening population.

Overlaying these issues are ethical and policy questions. Should asymptomatic elderly patients with incidentally discovered tumors undergo invasive follow-up when survival gains are negligible? Such scenarios sit uneasily with the Hippocratic principles of beneficence and non-maleficence. Furthermore, how do we justify the economics of deploying MCED in broadly screened, low-incidence populations, when cost-effectiveness is likely stronger in high-risk groups? For single-payer systems in the EU and UK, which must weigh cost-effectiveness at scale, the policy bar is high. Formal adoption will be contingent on long-term prospective studies that correlate stage-shift with improved cancer-specific or overall survival. In that light, the NHS-Galleri trial results anticipated in 2026 will be pivotal, providing the first large-scale, randomized, real-world data on whether MCED delivers on its promise. Until then, policy makers are unlikely to rewrite decades of public policy.

Another consideration in 2025 is the evolving genomic landscape. Policymakers may fold MCED into broader national strategies such as France’s Genomic Medicine Initiative 2025, Germany’s “Modellvorhaben zur umfassenden Diagnostik und Therapiefindung,” and England's “100,000 Genomes Project”, positioning MCED not just as a screening tool but as an enabler within larger precision medicine ecosystems. However, genomic data usage raises critical concerns regarding data privacy and ownership, especially considering GDPR. Clear regulations and robust safeguards will need to be implemented to maintain trust among clinicians and patients alike. MCED may prove transformative over a longer horizon, but here in 2025 the health policy and economics case remains to be made.

The first issue we need to discuss is prevention – because prevention is the best cure that we currently have. Science tells us that 40% of cancer cases are preventable. And yet only 3% of health budgets go into prevention.” - Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission

Conclusion

MCED testing offers a cautiously optimistic addition to the preventative care landscape, likely to serve as an adjunct to, rather than a wholesale replacement of, current programs. With fresh product launches coinciding with mixed trial results and regulatory scrutiny for some MCEDs, the field looks set for a period of realignment: targeted SCEDs for risk-stratified groups may gain early traction while MCED proponents await definitive, long-term outcomes (see figure 1). Incremental sensitivity gains from advances in sequencing and methylation algorithms, alongside emerging modalities such as fragmentomics and AI, may strengthen the clinical and economic case for MCED to evolve into a future gold standard for capturing cancers with no SCED pathway (ovarian, pancreatic, liver), or triaging populations for targeted SCED.

Yet, innovation risks exacerbating disparities: In regions struggling with basic screening, introducing genomic testing may widen the gap with countries like France with accelerated reimbursement pathways (e.g., the RIHN list). Ensuring health equity requires targeted infrastructure investment, increased health education and adapting to a more diverse Europe. The road to success will be paved not solely by scientific advances and good intentions, but alongside political and societal ones.

Note: The MCED sensitivities referenced above are generally lower than those reported in index publications and company-released data. This is due to differences in study design and population: some values reflect real-world, asymptomatic screening cohorts (with lower sensitivity for early-stage cancers), while others are drawn from case-control studies or select clinical populations (which often report higher sensitivity). Consider the context when comparing test performance across studies

Comments and opinions expressed by interviewees are their own and do not represent or reflect the opinions, policies, or positions of DeciBio Consulting or have its endorsement. Note: DeciBio Consulting, its employees or owners, or our guests may hold assets discussed in this article/episode. This article/blog/episode does not provide investment advice, and is intended for informational and entertainment purposes only. You should do your own research and make your own independent decisions when considering any financial transactions.

.png)